General processing description

Research and development work in many disciplines – biochemistry, chemical and mechanical engineering – and the establishment of plantations, which provided the opportunity for large-scale fully mechanised processing, resulted in the evolution of a sequence of processing steps designed to extract, from a harvested oil palm bunch, a high yield of a product of acceptable quality for the international edible oil trade. The oil winning process, in summary, involves the reception of fresh fruit bunches from the plantations, sterilizing and threshing of the bunches to free the palm fruit, mashing the fruit and pressing out the crude palm oil. The crude oil is further treated to purify and dry it for storage and export.

Large-scale plants, featuring all stages required to produce palm oil to international standards, are generally handling from 3 to 60 tonnes of FFB/hr. The large installations have mechanical handling systems (bucket and screw conveyers, pumps and pipelines) and operate continuously, depending on the availability of FFB. Boilers, fuelled by fibre and shell, produce superheated steam, used to generate electricity through turbine generators. The lower pressure steam from the turbine is used for heating purposes throughout the factory. Most processing operations are automatically controlled and routine sampling and analysis by process control laboratories ensure smooth, efficient operation. Although such large installations are capital intensive, extraction rates of 23 – 24 percent palm oil per bunch can be achieved from good quality Tenera.

Conversion of crude palm oil to refined oil involves removal of the products of hydrolysis and oxidation, colour and flavour. After refining, the oil may be separated (fractionated) into liquid and solid phases by thermo-mechanical means (controlled cooling, crystallization, and filtering), and the liquid fraction (olein) is used extensively as a liquid cooking oil in tropical climates, competing successfully with the more expensive groundnut, corn, and sunflower oils.

Extraction of oil from the palm kernels is generally separate from palm oil extraction, and will often be carried out in mills that process other oilseeds (such as groundnuts, rapeseed, cottonseed, shea nuts or copra). The stages in this process comprise grinding the kernels into small particles, heating (cooking), and extracting the oil using an oilseed expeller or petroleum-derived solvent. The oil then requires clarification in a filter press or by sedimentation. Extraction is a well-established industry, with large numbers of international manufacturers able to offer equipment that can process from 10 kg to several tonnes per hour.

Alongside the development of these large-scale fully mechanised oil palm mills and their installation in plantations supplying the international edible oil refining industry, small-scale village and artisanal processing has continued in Africa. Ventures range in throughput from a few hundred kilograms up to 8 tonnes FFB per day and supply crude oil to the domestic market.

Efforts to mechanise and improve traditional manual procedures have been undertaken by research bodies, development agencies, and private sector engineering companies, but these activities have been piecemeal and uncoordinated. They have generally concentrated on removing the tedium and drudgery from the mashing or pounding stage (digestion), and improving the efficiency of oil extraction. Small mechanical, motorised digesters (mainly scaled-down but unheated versions of the large-scale units described above), have been developed in most oil palm cultivating African countries.

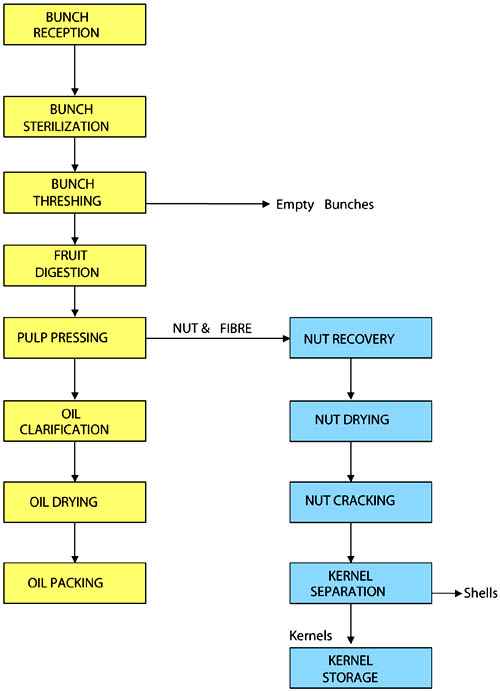

Palm oil processors of all sizes go through these unit operational stages. They differ in the level of mechanisation of each unit operation and the interconnecting materials transfer mechanisms that make the system batch or continuous. The scale of operations differs at the level of process and product quality control that may be achieved by the method of mechanisation adopted. The technical terms referred to in the diagram above will be described later.

The general flow diagram is as follows:

PALM OIL PROCESSING UNIT OPERATIONS

Harvesting technique and handling effects

In the early stages of fruit formation, the oil content of the fruit is very low. As the fruit approaches maturity the formation of oil increases rapidly to about 50 percent of mesocarp weigh. In a fresh ripe, un-bruised fruit the free fatty acid (FFA) content of the oil is below 0.3 percent. However, in the ripe fruit the exocarp becomes soft and is more easily attacked by lipolytic enzymes, especially at the base when the fruit becomes detached from the bunch. The enzymatic attack results in an increase in the FFA of the oil through hydrolysis. Research has shown that if the fruit is bruised, the FFA in the damaged part of the fruit increases rapidly to 60 percent in an hour. There is therefore great variation in the composition and quality within the bunch, depending on how much the bunch has been bruised.

Harvesting involves the cutting of the bunch from the tree and allowing it to fall to the ground by gravity. Fruits may be damaged in the process of pruning palm fronds to expose the bunch base to facilitate bunch cutting. As the bunch (weighing about 25 kg) falls to the ground the impact bruises the fruit. During loading and unloading of bunches into and out of transport containers there are further opportunities for the fruit to be bruised.

In Africa most bunches are conveyed to the processing site in baskets carried on the head. To dismount the load, the tendency is to dump contents of the basket onto the ground. This results in more bruises. Sometimes trucks and push carts, unable to set bunches down gently, convey the cargo from the villages to the processing site. Again, tumbling the fruit bunches from the carriers is rough, resulting in bruising of the soft exocarp. In any case care should be exercised in handling the fruit to avoid excessive bruising.

One answer to the many ways in which harvesting, transportation and handling of bunches can cause fruit to be damaged is to process the fruit as early as possible after harvest, say within 48 hours. However the author believes it is better to leave the fruit to ferment for a few days before processing. Connoisseurs of good edible palm oil know that the increased FFA only adds ‘bite’ to the oil flavour. At worst, the high FFA content oil has good laxative effects. The free fatty acid content is not a quality issue for those who consume the crude oil directly, although it is for oil refiners, who have a problem with neutralization of high FFA content palm oil.